Tanzir Ahmed Montaisir /Bangladesh

Mobile phones are vital today—used for communication, education, banking, shopping, and entertainment. For children, they offer online classes, apps, and creative tools, along with cartoons and stories for fun. But overuse is dangerous: it causes eye problems, poor sleep, lethargy, irritability, mental instability, and distracts from studies, play, and social life. Children lose touch with nature, suffer isolation, weak family bonds, disinterest in learning, and face rising health issues. A viral video in Bangladesh showed a child violently attacking his mother to take her phone—an alarming sign of addiction. Many parents, to keep children calm at meals, bedtime, or work, hand them phones. In urban life, apartments often feel like cages: children return from school only to remain confined indoors. With few playgrounds and limited parental time, they are deprived of outdoor play and nature.

I met photographer Shahnewaz’s three children, whom he regularly took to playgrounds and nature to protect them from mobile addiction. I saw 10-year-old Shafayat, uninterested in studies or sports, lost in mobile games; 8-year-old Afif, suffering eye problems; and 14-year-old Jihad, a victim of family abuse—all due to phone addiction. In a workers’ housing building of 40 families, countless children live like prisoners—confined indoors by parental busyness, lack of playgrounds, and insecurity—making them easy prey to mobile addiction.

I have been working with this crisis, which started as a class project in Chittagong, Bangladesh. My choice of topic stems not only from a wish to raise awareness but also from a deep fear for myself and future generations. This is not just Bangladesh’s crisis, nor Asia’s, nor defined by race—it is a global issue. Here I explore children’s mobile addiction, its harmful effects, and the possibilities of a free childhood filled with growth and creativity. This ongoing work is not only about children—it is a document of our present and future.

Tanzir Ahmed Montaisir, 26, is an emerging photographer whose work reflects curiosity, observation, and a deep connection to life around him. Currently enrolled in a one-year Career Development and Masterclass program at Chittagong VOHH Institute, he is exploring visual storytelling while shaping his own creative identity. With roots as a diploma agriculturist, Tanzir finds inspiration in nature, people, and the subtle emotions of everyday life. Though he has yet to enter competitions, his journey is driven by learning, exploration, and the desire to translate moments into meaningful images.

In that workers' housing building, a child walks out of his room with a mobile phone in his hand. In the next room, a few children are sitting and chatting with books and papers. Different worlds in the same place—on one side, the attraction to technology, on the other, the chatter of paper and pen. The photo was taken on August 20, 2025, from Ruby Gate in Chittagong city.

Wafika, 10, is a creative young girl whose childhood was once filled with colours, brushes and imagination. Her father lives abroad, while her mother is a housewife manages the home and looks after her two sisters. With no safe playground nearby, Wafika spends most of her time between school and home, rarely getting the chance to go outside. The photo was taken on August 16, 2025, in Firingibazar, Chittagong.

Two friends, madrasa students, have come to Patenga Beach with their families for a vacation, but their mobile phones don't seem to be leaving them behind there either. The photo was taken on August 19, 2025, from Patenga Beach, Chittagong, Bangladesh.

Sarfaraz has an exam the next day, while his younger brother Turaj has not yet been admitted to school. As Sarfaraz studies, Turaj often calls him to play. When he cannot find his brother, he sometimes occupies himself with his mother’s phone, leaving the household undisturbed. The photo was taken on August 18, 2025, in the Pahartali Akbarshah Society area of Chittagong, Bangladesh.

In the picture, Sarfaraz and Turaj sit quietly at the table on a holiday, looking heartbroken, while the other family members remain absorbed in their own work. With no one to spend time with them or take them to the field to play, the children turn to mobile phones—falling into addiction fueled by family neglect. This photo was taken on August 23, 2025, in Akbarshah, Chittagong, Bangladesh.

Four-year-old Turaj squints and closes his eyes while walking into a green field. Due to his mobile addiction and constant screen time, he struggles to tolerate the brightness of the sun. This photo was taken on August 20, 2025, in Pahartali, Chittagong, Bangladesh.

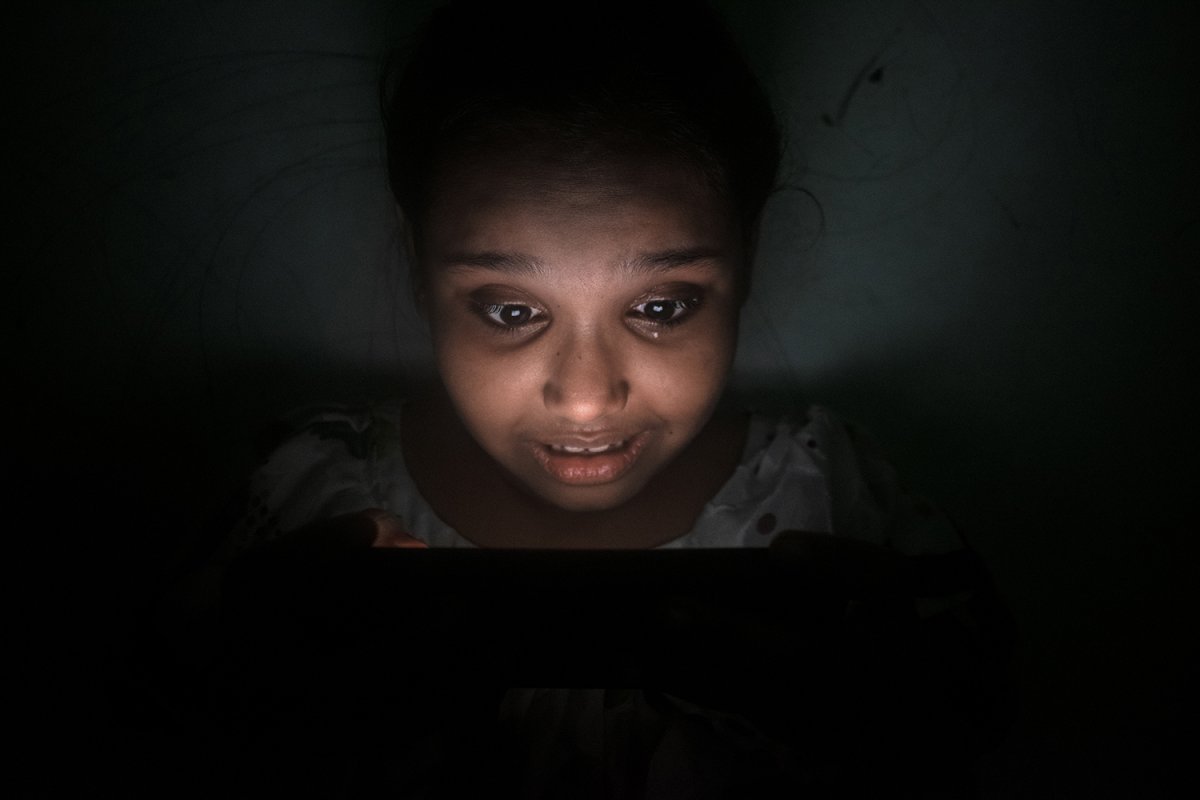

Eight-year-old Zulfikar is a wicked child. With his father working away from the city, his mother manages him and his two sisters alone. Whenever he gets the chance, he turns to his mobile phone. As soon as his mother steps away, he starts playing games—peeking occasionally to check if she is coming. The photo was taken on August 16, 2025, at the Akbarshah Railway Society in the Pahartali area of Chittagong city, Bangladesh.

After returning from madrasa, Shafaat often turns to mobile games. One day, while he was playing, the phone rang and his mother took it away. Surrounded by toys, he showed no interest in them; instead, he sat quietly on the floor—withdrawn and disappointed. The photo was taken on August 18, 2025, in Oxygen, Chittagong, Bangladesh.

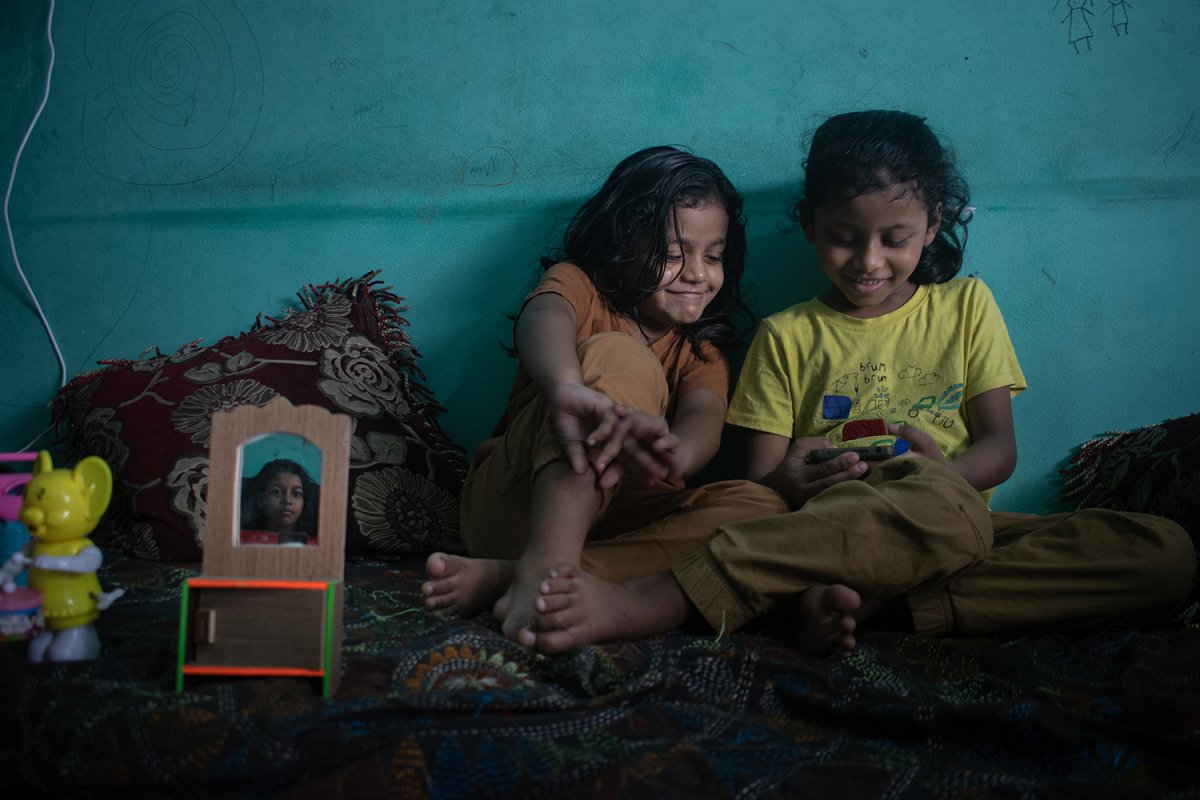

Wafika and Warda watch cartoons on their mobile phones after completing their homework and studies on a school holiday. In the toy’s mirror, the reflection of their elder sister, Wasika, appears as she waits to receive the mobile phone. The photo was taken on August 16, 2025, in Firingibazar, Chittagong, Bangladesh.

10-year-old Shafaat is absorbed in his mobile phone screen while eating after returning home from his madrasa classes. Behind him, his 8-year-old brother Rafayat is looking out the window. The photo was taken on August 18, 2025, in the Oxygen area of Chittagong city

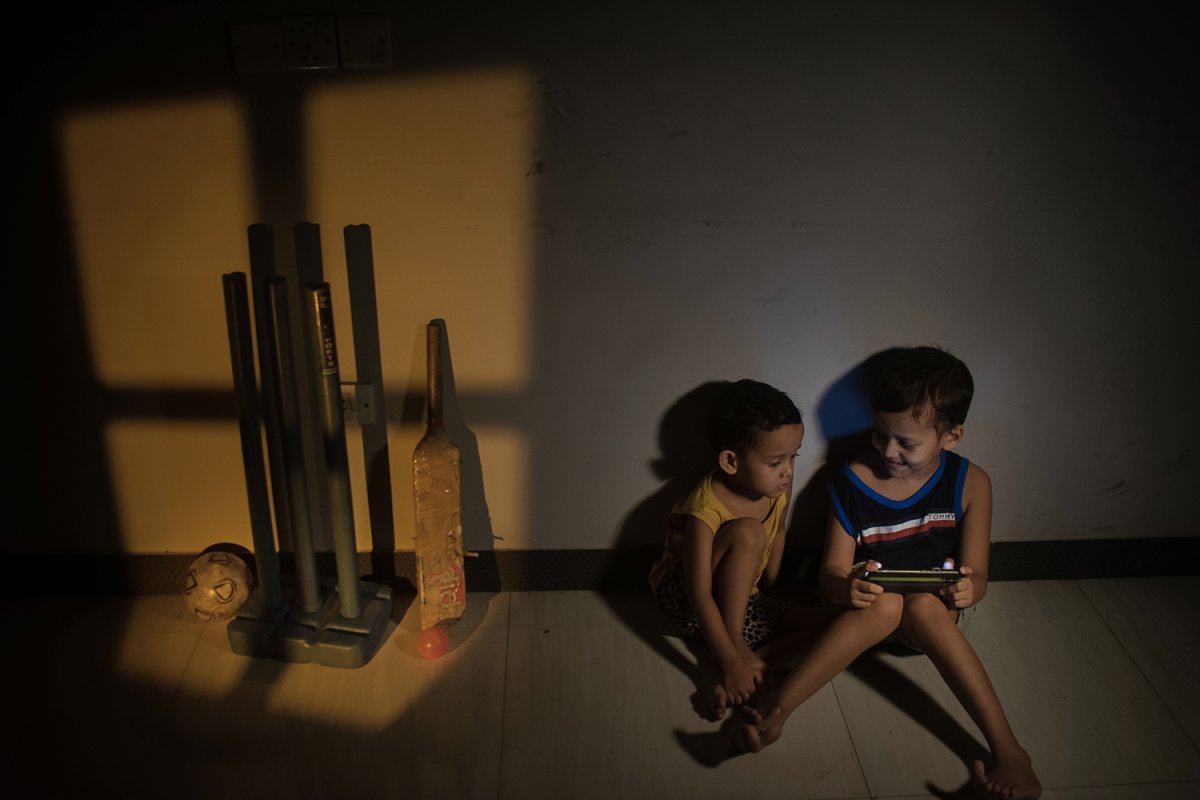

Seven-year-old Sarfaraz and four-year-old Turaj, sons of an expatriate father, live with their mother, grandparents, and uncles in a joint family. With no one free to take them outside, they spend the afternoon absorbed in mobile phones, while a bat and ball beside them seem to silently call them to play. The photo was taken on August 17, 2025, in the Pahartali Akbarshah Society area of Chittagong, Bangladesh.

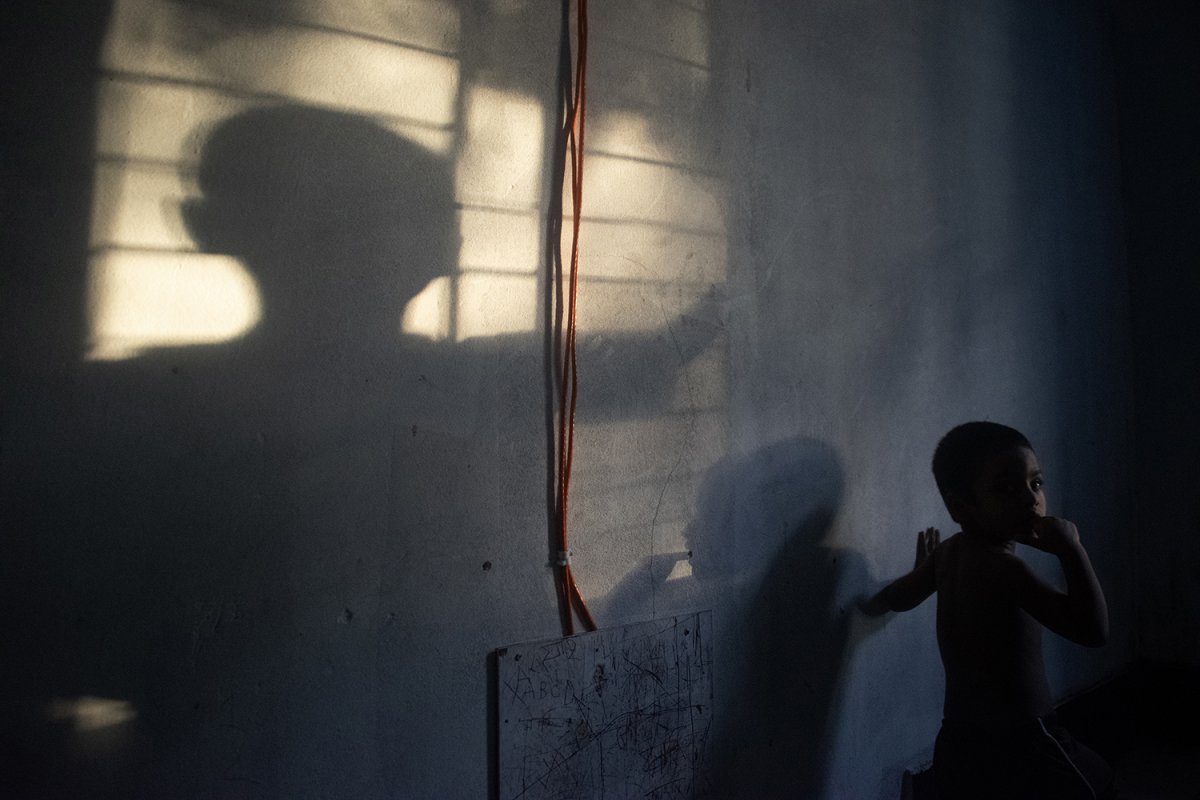

Jihad, 10, a class six student, is the son of a laborer who works as a painter. In his free time, Jihad immerses himself in mobile games. One night, while Jihad was supposed to be studying, his father—who is often away from home for work—found him playing on his mobile phone and, in anger, tried to beat him. His sister Sanju, also seen in the picture, is similarly addicted to mobile phones. This photo was taken on August 20, 2025, in Halishahar, Chittagong, Bangladesh.

Photographer Shahnewaz regularly takes his three children to a playground surrounded by greenery and exposes them to the morning sunlight, both to protect them from the harmful effects of mobile phones and to support their physical and mental development. In the picture, Hossain (9) and Imran (8) are playing football with their friend Mobashir (8), while their sister Noor Fatima (3) watches from behind. This photo was taken on August 15, 2025, in Agrabad, Chittagong, Bangladesh.

Words from

Mohammad Shahnewaz Khan

Photographer and mentor (VOHH Institute of Photography)

Although the Masterclass was originally planned for one week, I extended it to ten days. For seven days, I conducted intensive, hands-on sessions averaging 16 hours a day, while the remaining days were devoted to refinement and polishing.

The entire course was structured in three phases:

Phase One – Developing technical knowledge, practical skills, and a deeper understanding of photography, alongside guidance on mastering different genres.

Phase Two – Focusing on the single image. Here I emphasized diverse approaches and philosophies, from people and portraits, landscapes and nature, to photojournalism, conceptual work, metaphor and symbolism, abstraction, and beyond—explored from both artistic and journalistic perspectives.

Phase Three – Concentrating on the core: storytelling and documentary practice.

I gave my student day and night, unfolding each stage—from scriptwriting to shooting. I stood by him in solving every problem, even reviewing his work directly in the field (while maintaining safe distance). This gave him extraordinary inspiration and helped him quickly find his rhythm.

I personally taught him project description, naming, writing captions, and crafting project proposals. In short, I provided the sincerity I myself never received during my own student life, ensuring he did not face the same obstacles I once did. I condensed what is usually a year-long process into just 7–10 days—sharpening not only his photography but also his writing and research. With this formula, he can develop countless projects in the future and carry forward his ongoing work.

Alongside, I emphasized resilience, building relationships with subjects and their families, practicing candid and conceptual approaches, and much more that I will not detail here. And yes—before beginning the Masterclass, I entered into an agreement with him.

Kind Regards

Mohammad Shahnewaz Khan

I initiated a week-long Masterclass project with the aim of nurturing dedicated photography students to grow internationally. Today, I am sharing the work of its first student, Muntasir, who became a regular in photography a few months ago. This effort reflects my commitment to my students and is intended to reach photography enthusiasts, photojournalists, editors, and researchers at home and abroad.

Although the Masterclass was originally planned for one week, I extended it to ten days. For seven days, I conducted intensive, hands-on sessions averaging 16 hours a day, while the remaining days were devoted to refinement and polishing.

The entire course was structured in three phases:

Phase One – Developing technical knowledge, practical skills, and a deeper understanding of photography, alongside guidance on mastering different genres.

Phase Two – Focusing on the single image. Here I emphasized diverse approaches and philosophies, from people and portraits, landscapes and nature, to photojournalism, conceptual work, metaphor and symbolism, abstraction, and beyond—explored from both artistic and journalistic perspectives.

Phase Three – Concentrating on the core: storytelling and documentary practice.

I gave my student day and night, unfolding each stage—from scriptwriting to shooting. I stood by him in solving every problem, even reviewing his work directly in the field (while maintaining safe distance). This gave him extraordinary inspiration and helped him quickly find his rhythm.

I personally taught him project description, naming, writing captions, and crafting project proposals. In short, I provided the sincerity I myself never received during my own student life, ensuring he did not face the same obstacles I once did. I condensed what is usually a year-long process into just 7–10 days—sharpening not only his photography but also his writing and research. With this formula, he can develop countless projects in the future and carry forward his ongoing work.

Alongside, I emphasized resilience, building relationships with subjects and their families, practicing candid and conceptual approaches, and much more that I will not detail here. And yes—before beginning the Masterclass, I entered into an agreement with him.

Kind Regards

Mohammad Shahnewaz Khan

Photographer and Mentor ( VOHH Photography Institute )